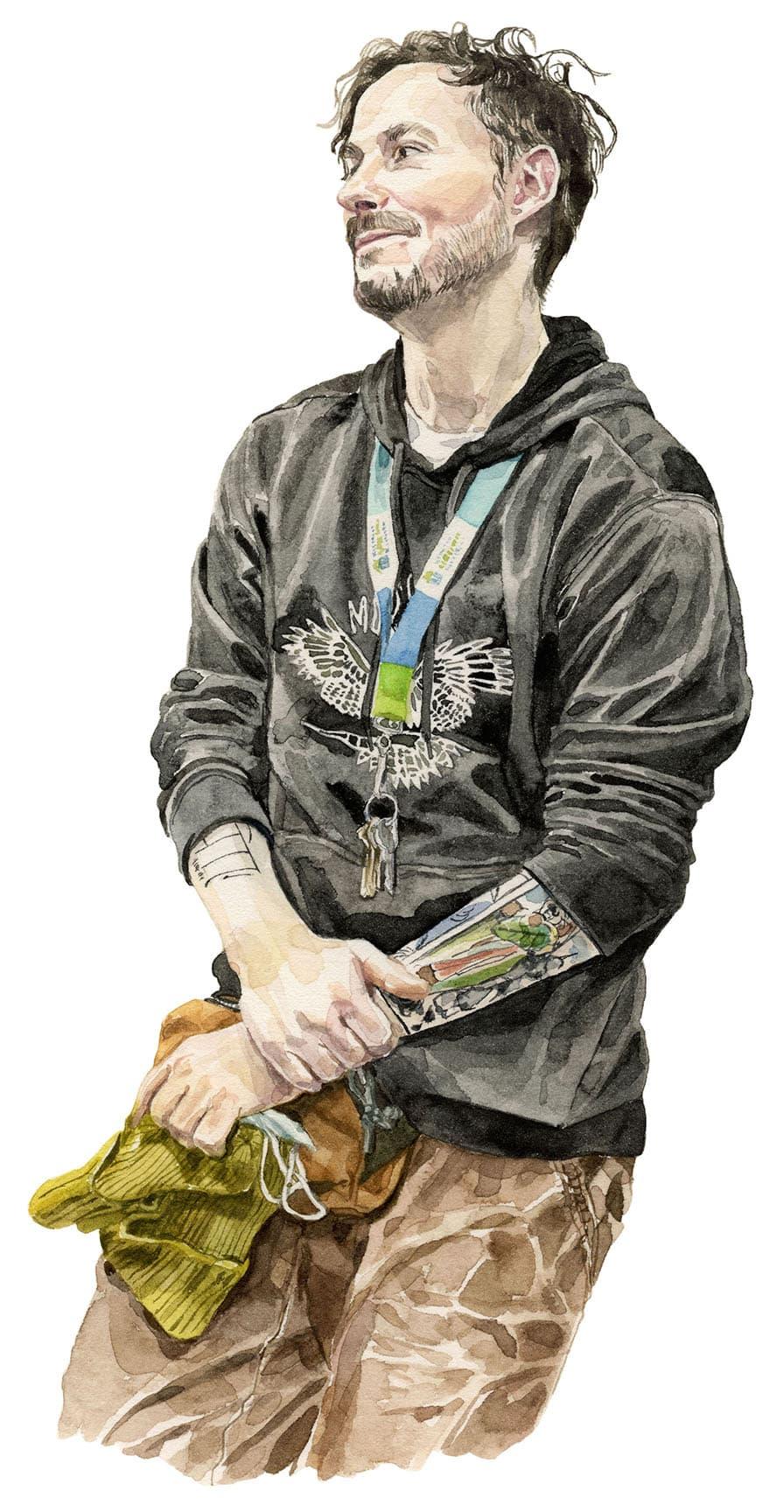

Noel

A 39-year-old community health worker at Moss Park CTS. Interviewed in August, 2025 in Toronto and edited for clarity. Illustration by Melinda Josie © 2025

I prioritize sleep. It has always been a part of my life to care about the room in which I sleep, and some of the practices leading up to [sleep]. I've set up my life in a way where the conditions for sleep are pretty routine. Actually, I guess as a kid too, I found nighttime quite sacred.

I grew up with siblings in a pretty social household. And even when I shared a room with my twin brother, nighttime was quite sacred. I've always been a night owl, so [I stay] up late, but I think of sleep as an indulgence, and enjoy and plan around [getting] a good, long sleep.

[My dream life is] quite lively. I would say in general, over the last three to four years [I’ve had] a more active engagement with my dreams. My brother has really gotten into talking about and sharing dreams over the last seven or eight years. And so that has probably enhanced some of my awareness of my dreams. The emotional tenor of the dreams is pretty much in keeping with my life. So, if there's anxiety and stress, that's carried through to the dreams. There's a pretty healthy relationship right now, as I understand it, between my dream life and my day-to-day life.

There was a time—maybe, like, late 20s through early 30s—where I was not recalling dreams much at all. I can't think why that was. It's a time when I started reading Freud and caring about psychoanalysis and the unconscious[laughs]. So, I guess they were hiding.

When I started working at Moss Park, I had recurring dreams. In the dreams I couldn't tell whether I used fentanyl or not. I'm sitting at a table. I had either just done a shot, or I was preparing to do a shot, or I was cooking up a shot. Often it felt like it [took place at] Moss Park, but there were a few where it wasn't. But [there were] recognizable people from the community and staff.

In the dream, I'm asking myself, “Shoot, wait, do I use?” I'm me in the dream, like as a staff [member] working at Moss Park. But what I can't tell is whether I use or not. And there's a kind of panic about whether I'm gonna need emergency help—Naloxone and a 911 call—or not.

I don't have a lot of lived experience with injection drug use. And so, when I started work, there was a curiosity about what it would feel like to be high on fentanyl – what opiates feel like in general. So, I think there was a curiosity piece to it. But there's quite there's an anxious piece to it, too. When I was learning about safe injection sites and reading about fentanyl, there was a real sense that you could accidentally sniff some and then overdose, because of how strong it is. We are quite careful at work—washing your hands if you've touched the drug. And so, I think there was fear about that.

[There were] a couple of instances in the first few months when I worked there when a community member went to stick [one of the nurses] with a needle that had fentanyl in it. And so, as a staff, we had to address that concern: What –would –happen –in –that –emergency –situation –kind-of planning. So, I imagine that was a piece of my psyche at the time. I was a little shocked. When you're running a service that is unique and under-resourced, some of these things come up in real time and you realize, “Oh, there's a potential emergency here that we have to plan around.” And of course, there's lots of safeguards in place. Staff are really careful with handling drugs. But we hadn't planned so much around this. I think that incident precipitated a lot of thought around tolerance. And it strums the cords of my curiosity as well, because if you have a curiosity around what it would feel like to be high on opiates, that sense that there's also a risk here that could happen to you, lights that fire a little bit.

I feel the dream is also visualizing a personal anxiety—or maybe a personal conflict—that I had in the work, which is: I was an outsider coming into this community with no lived experience and with not a lot of training. I was getting the question, “What brought you to this work? Why are you here in this kind of a job?” And I found that question hard to answer. I had my political and my ethical reasons why I think it's an important service and why the community deserves access to it. But I couldn't articulate a personal claim to why I'm in that job. I think some of my own discomfort around not answering that question is in that dream as well.

In a few of the dreams, I've literally just done a shot and then I'm waiting to feel it. I'm like, “Wait. Shit. Do I do fentanyl?” There's a panic. There's a sense that something needs to be done. Something is gonna follow. I's a nebulous feeling, like “Am I a drug user? Do I have experience in what I've just done?” Or “Is this something I'm familiar with? Do I know what happens next? Do I know what comes next?”

I have less anxiety at work [now]. I feel more comfortable in knowing what to do. And [the dreams have] lessened. Now that [I have] shared more about my own history with community, there's less of a sense that, in order to have a place here, I need to be an injection drug user. There's actually a lot of different ways tobuild relationships and get close with others. So maybe the dream is asking that question around competency and belonging—“How much of me is here?” It takes me a while to share with others. At first, I thought “They don't need to hear about my life; it's their lives that are hard. So, I'll just listen.” And so maybe the dream is, like, “You can't just listen, you've already done the shot, you're already working, you're already in the injection room.” And so maybe over time, I've just done the reciprocal thing that you're supposed to in building relationships.

I still have work dreams, but it's more about the space where is the service going to take place. And I think that has more to do with fears over the continuation of the service. But it's less about me actively doing drugs.

I have just one [other dream I want to share]. It is the most impactful dream from my childhood. It's a bizarre one. I was probably 8 or 9, maybe 10. This was shortly after my mom's best friend—a dear friend of the families—had passed away. In the dream, I'm in the computer room of my childhood home in Prince George. And there's a lineup of people who are not familiar to me, but they're going down a hidden stairwell from the computer room.

It's a procession that I identify in the dream as having to do with the funeral service of my mom's friend who passed. I follow them down and there's a feeling of dread. I sense it's a nightmare. I don't like what's happening. But I go down, following the lineup, and eventually I look down and I see a potted plant and it's a witch's face. A very wrinkly witch's face is the plant head. Her head is the plant. And I stare at it. And a piece of gum drops from my mouth and lands in the potted plant. And then the witch’s eyes are squinting and closed, and she says, “Who snapped my fingers?” And then I wake up in a panic. It's the scariest thing that I've ever experienced. I immediately tell my brother. We were probably sharing a room at that time. Bunk beds.

I don't really know what to make of it, except that the witch's face is scary. It’s blue and very wrinkly, like a prune or a grape. The dream makes her face so realistic, but it is such a cartoonish image of this plant pot witch head. But the fear was real. It was really overblown. It was terrifying. Her eyes were closed. And she was turned to the side, like she's addressing the room, but I'm feeling summoned by the address anyway.

The computer room that was like a sanctuary of mine. I’d play solitaire or going into the computer room to listen to music or play games or something.

It was very impactful and sad to experience the loss of that family friend. I could sense it was really important to our social circle or whatever. But I don't know what the witch is about. Or the gum in my mouth. Or the snapping of the fingers. Just prior to [the dream], we went on a family trip, and over the course of that trip, my sisters were cracking their knuckles and taught me how. So that's an association [I have] to the snapping of the fingers. But that's not what it meant to me as a kid. It just felt like a drastic thing to say, [something] that I was being accused of.

The friend that died worked with my mom at the college. I knew her as my mom's closest friend. She was funny. She used to call me Toad. She would call all the kids Toad. “Come on, Toad!” Yeah, I dunno. When my mom got the news, it was probably the first time I've ever heard my mom full bodily cry, like heaving sobs, inconsolable sadness. So that's a piece of my memory.

As a child I would cry a lot about dying and be unable to go to sleep because I was thinking about death. That was a recurring anxiety of mine—and an ongoing one. Waking up to the fact of mortality and being unable—unwilling—to accept it. I have vivid memories from when I'm maybe five or six and my mom talking me through that at, like, midnight.

In my daydreams, I always return to summers in Prince George. It's like a Saturday. I’m probably, like, 9 or 10. I can hear one of my parents mowing the lawn. I can hear birds. I'm in my bed, but close to a window. I can be where I am for as long as I want. It's a very cozy feeling, very nostalgic. Like if I see sun coming through a window and a bit of breeze and birdsong, I'll go right back to that place.

My brother has had some exquisite, devastating dreams that he's shared with me. World ending dreams. High pathos dreams. Sometimes it's hard to distinguish what's my memory and what's his. But there's a few [dreams] in particular that he brought to me and it has been, like, “Carry this because I entrust you to dwell with these images.” There's something special about sharing dreams. I've never talked about the potted witch dream outside my family, so sharing it in this way feels new. Like putting it somewhere. That feels special. Having a conversation about that dream has changed it somehow.

I feel very attached to Moss Park. I came [into the community] at a time in my life where I was feeling very isolated and a little bit lost and a little bit adrift and hopeless. A lot of isolation. A career path change. I landed at Moss Park in need of community. Luckily enough it’s a place where community is such a currency. And as I opened up to Moss Park, it's felt like such a landing place, such a strong firm ground. It holds a lot of my political beliefs and so it's a place I can go and exist in my day-to-day work and feel like I believe in it. And then it's also infinitely bizarre and joyful and sad. Just full of life. Overfull. Sometimes you need to get away from it because it's too much. But it's really refilled my sense of purpose and belonging.